At Commons Network, our work is deeply embedded in issues of global (in)justice. As we do research and politically organise around topics such as digital commons in the Netherlands and degrowth on a Pan-European scale, we are constantly reminded that democratising the economy here and now needs to go hand in hand with the liberation of communities and workers worldwide.

For this blog, we zoom in on the issues of energy transition and digital economy for one of the many sacrificed zones in the global capitalist economy: the Kivu, in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). If we go upstream through the global supply chains and through the history of colonial exploitation and extractivism, what do we learn about a just energy and digital transition? The digital and energy transition are embedded in our growth-centred capitalist economy, as such they rely on the ever-increasing extraction of materials and the exploitation of communities in the Global South.

Authors: Diane Golenvaux, Ayoub Samadi, Alba Garcia

We share information on the armed conflict and humanitarian crisis that plays out in the region and lay bare the economic interests and political (in)actions that enable this violence to endure. We interviewed Pacifique Mushubusa from Youth for Peace DRC, as well as Komeza M. Ngendakumana and Kyenge Kisoke from Comité Ujamaa, Pan-Africanist organisation based in Brussels.

Going upstream: Colonial violence and its legacy

The DRC is said to be under the ‘resource curse’ or the paradox of the plenty: although it is considered one of the richest countries in terms of natural resources, its citizens are among the poorest in the world.[1] To this day, there are between 120 and 140 armed groups in the East fighting over mineral resources, committing mass killings and sexual violence. About 6 million people are internally displaced, and an estimated 6 million people have been killed by this conflict that has not been resolved for the past thirty years.[2] The region holds critical reserves of metals and rare earth minerals, such as cobalt and coltan[3] which are in increasing demand, and the plunder and exploitation are further enabled by the ongoing insecurity.[4] Although ties between the armed rebel group M23 and Rwanda are well documented (notably by the UN), Rwanda still receives military funding from the UK, US and France, and has trade agreements over raw minerals export with the European Union.[5]

For over a century, the people and natural resources of the DRC have been systematically exploited for the benefit of the few – mostly the political and foreign capitalist elite. This pattern was established under the colonial rule of Belgian King Leopold the II, through the enclosure of land, militarization, the enslavement of the local population and raw materials’ extraction and export (from mostly rubber in the 1890s to the development of the mining industry in the 1900s). As the Belgian State took ownership over the colony in 1907, this colonial capitalist model of forced labour, extractivism and foreign capital accumulation continued. Despite Independence and its promises in 1960, Mobutu Sese Seko was backed into power by Belgium and the US, and economic sovereignty was not on the agenda for his thirty years’ rule.[6]

The conflict in the Kivu dates back to 1994, as the genocide against the Tutsis pushed two million Rwandese refugees to the DRC. This period marked the apparition of armed groups and militias in the region, and the beginning of numerous massacres.[7] In the context of this refugee crisis in the East, ethnic and political tensions escalated into the First Congo war (1996-1997) and a coup against Mobutu’s regime backed by neighbouring countries Rwanda and Uganda. As their ally at first, Laurent-Désiré Kabila took over the Congolese government, but these tensions persisted leading to the second Congo war (1998-2003) where rebel groups were again backed by neighbouring countries.

According to the UN report of Human Rights violations, “the struggle between different armed groups for control of the DRC’s natural assets served as a backdrop for numerous violations directed against civilian populations”.[8] During the two wars, mass killings, sexual violence, attacks on children, forced labour and other abuses by foreign armies, rebel groups, and Congolese government forces are documented. Pacifique from YFP explained that Congolese civil society has been asking for a Criminal Court to take place, in order to hold the people responsible for the crimes committed, to examine the claims of genocide and to build sustainable peace in the Kivu. But impunity prevails, and crimes of mass killings and sexual violence continue to take place up to today without any reaction from the international community. Armed groups that hold ties to Rwanda persist in the region and commit massacres, such as the M23 rebel group which led a first armed rebellion in 2013 and has invaded parts of the Kivu since 2022.[9]

The violence committed in the DRC throughout history for the economic interests of governments and foreign corporations, combined with the general indifference for the Congolese lives that bear the costs, has pushed civil society organizations to name it “the silent genocide”. Our interviewees from Youth For Peace and Comité Ujamaa both emphasised this perspective. In Komeza’s words: “It started much longer than 10 years ago, back to the Berlin Conference (…) the congolese people are being exterminated in impunity; without any sanctions, noise or visibility”. “It’s as if Congolese people are not humans (…) it’s a genocide that we see in the North-Kivu, under the silence of the international community” said Pacifique.

Artisanal miners at Shabara mine near Kolwezi on October 2022[10]

Mining in the DRC

When we think of mining, we usually visualise large machinery organised by multinational corporations. However, the reality is that approximately 60% of citizens in DRC rely on mining and 90% of those are artisanal miners. [11] Artisanal miners have minimal equipment and work under hazardous, risky, and unacceptable conditions. [12] For instance, tunnel collapses have been widely documented in artisanal mines. Many citizens have been displaced, either by multinational corporations or armed groups (seeking to enlarge their mining activities), and are left with no other choice but to accept these unjust working conditions in order to survive.

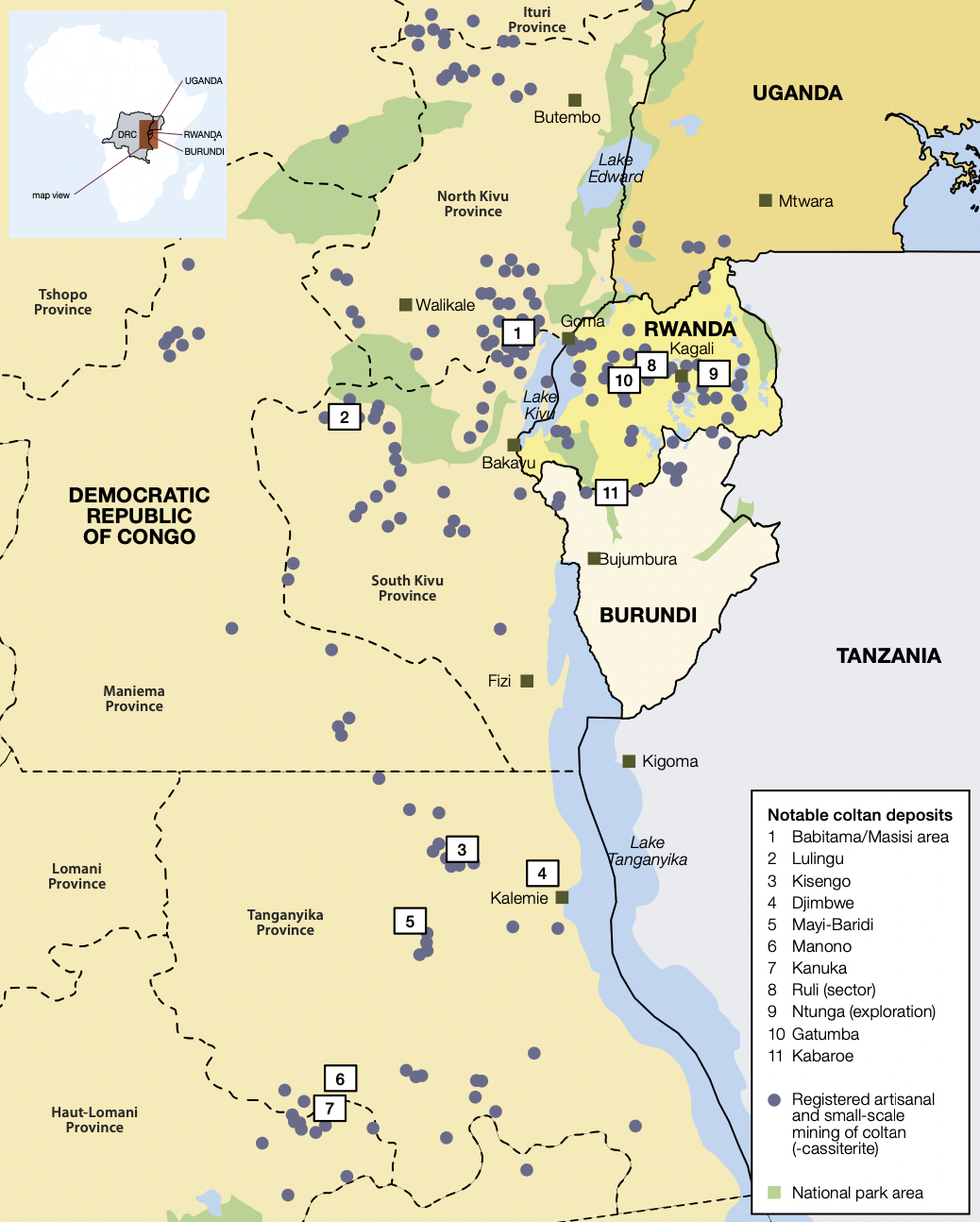

On top of that, citizens forced into digging by displacement are exploited by intermediaries (négociants) who negotiate mineral sales and supply trading houses (comptoirs) with conflict minerals. The rare mineral supply chain is opaque and complex. After ‘comptoirs’ receive rare minerals, international companies then transport the ore directly to the destination country. However, minerals are also smuggled through Uganda and Rwanda to overseas processing facilities.

Registered artisanal and small-scale mining of coltan in DRC

The complexity of the supply chain enables forced labour from vulnerable groups such as poor children and women. There are approximately 40,000 child and teenage miners in the DRC who dropout of school (or have never had the opportunity to attend) and resort to mining to make a living. In the process, they are vulnerable to child traffickers and recruitment by armed groups – which has become routine at Mukungwe coltan mine in South Kivu.[13]

“You can imagine a Congolese who lives in this environment, who sees his country’s minerals being exploited, who is a victim of even the fact that his territory has minerals.” Pacifique clearly states: “that’s not fair.” The Congolese government acknowledges this and has made attempts at tackling this, especially in the Mining Code of 2017 which penalized the use of child labour. However, child labour is still a prevalent issue; the quantity of rare minerals mined through child labour remains uncertified and untraceable in the supply chain. This is why there is no such thing as clean supply chains for cobalt and coltan.

Growth at all cost: the ‘green transition’ and ‘digital revolution’

A not-so green transition

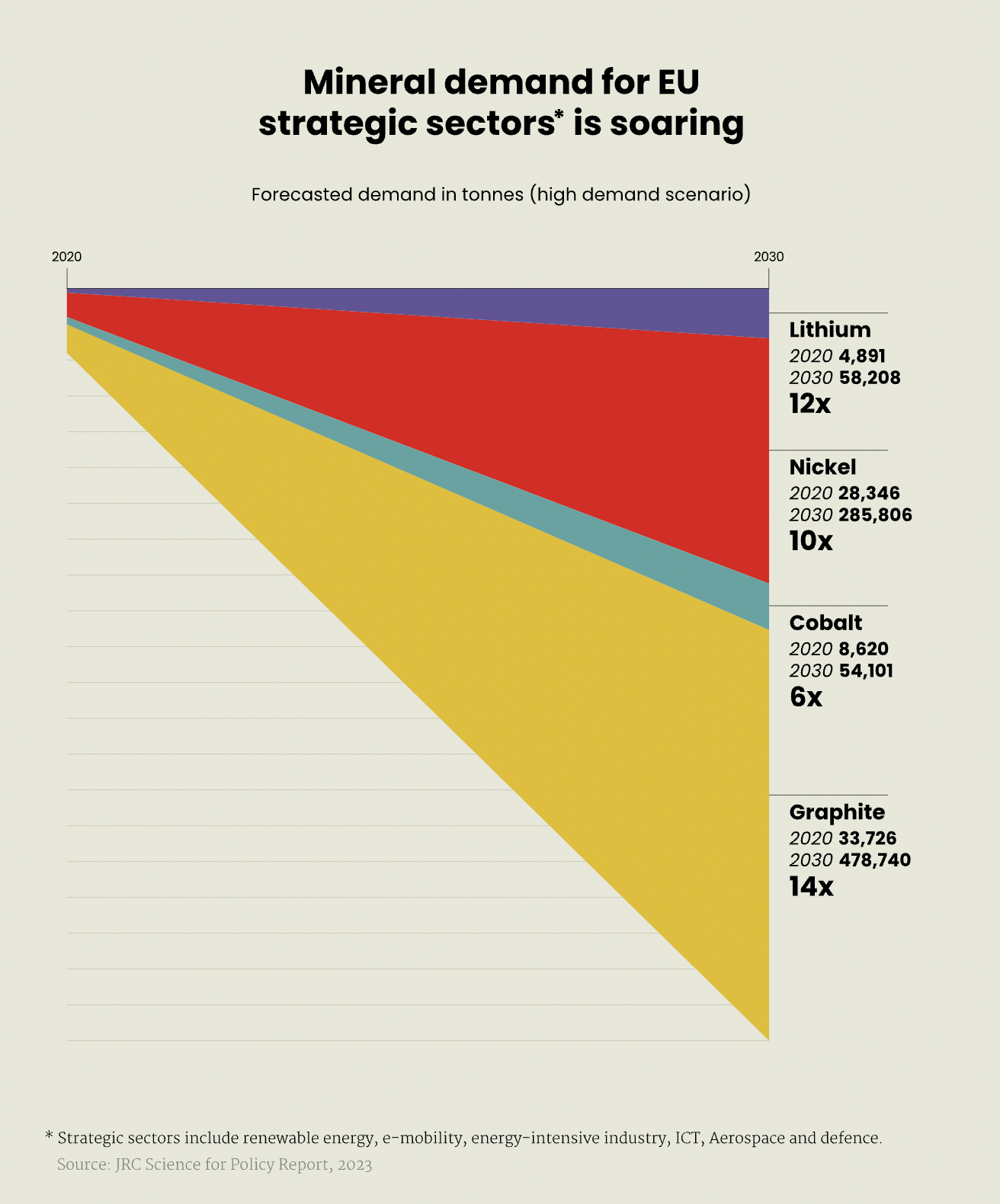

The transition toward renewable energy sources is considered necessary to stay within planetary boundaries. The political and public discourse around the energy transition is centred around the increased use in rare mineral technologies. This is the case in the European Green Deal and the 2015 Paris Agreement. With the market shifting towards renewable technologies, the demand for the raw materials used for their production has never been higher and more pressing. Phrases like ‘scale up’ and ‘accelerate’ are common to the language used in relation to the production and development of rare mineral technologies.[14]

Around 30 rare minerals are necessary for the energy transition. [15] Without cobalt there are no batteries or electric vehicles. Without copper, there are no energy storage systems and infrastructure for renewable energy. With the urgent need to transition towards renewable energy, we can expect an increase in the use of rare minerals. Indeed, to reach the 2°C global temperature target set out by the Paris Agreement, rare mineral supply would need to quadruple by 2040. [16] The DRC is a key contributor to reach climate objectives. In fact, 68% of Cobalt and 36% of Tantalum imported to the EU are from the DRC.[17]

Growth in demand for selected minerals from clean energy technologies by scenario, 2030 relative to 2020. [18]

Rather than reducing energy consumption, experts are saying we are adding energy to the global matrix. [19] Although we are increasing the use of renewable technology, the overall energy use is increasing. This is because the global economy is not organised around social needs and planetary boundaries, but rather around the imperative of economic growth. Hence, industrial production and consumption is under pressure to grow infinitely, in order to create sufficient capital accumulation to stabilise our economy. However, this imperative, or dogma of growth, has been proven to be irreconcilable with climate goals. This tension becomes ever clearer once we realise that 50 to 60% of extracted minerals end up in batteries of privately owned cars, rather than wind turbines or solar panels. Indeed, the EU is focused on mass producing electric vehicles for individual private use, proposing a climate solution through limitless consumerism instead of reduction of material use.

Efforts like the European Battery Alliance seek to capitalise on the market and industry potential of renewable energy sources like batteries.[20] However, during our interview with Pacifique we were told that increased mineral exploitation “has created effects on the land, on agriculture, on rivers that produce fish for example, rivers that have been infected by mineral-related materials […]Even access to drinking water is becoming very complicated.” Yet, this side of the equation is often dismissed; rather, the focus seems to be on establishing a resilient supply chain to bolster the production of rare mineral technologies. The EU Critical Raw Material Act, drafted particularly for this concern, seeks to increase domestic European production of raw materials and to secure a diversification of material providers through trade agreements in order to “meet its [EU] 2030 climate and digital objectives”.[21]

In particular, the EU prioritises resource-intensive growth to fuel its low-emission industries. To do so, it utilises global trade to secure access to raw materials. [22] This perpetuates a neocolonial extractivist economic model; the environmental impacts of the EU’s own consumption are displaced to DRC where the increased demand for ‘green’ energy is exacerbating displacement, land disputes, and environmental degradation. According to Kyenge, “transition, as we understand it, is only about solving problems elsewhere, not in the DRC.” Yet, as the global North rushes to mine critical minerals for the decarbonization of the global economy, the rights of communities in DRC must be at the forefront.

Digitalisation

Besides the energy transition, digitalisation also plays a big role in increasing the demand on raw materials. The ‘Digital Decade’ is a set of targets set out by the EU that prioritise the development of sustainable digital infrastructure and seek to digitise public services and data.[23] Practically speaking, this migration of data to the digital requires powerful systems that can manage its processing and storage. AI has emerged as an excellent tool to do this. However, increased processing power and sophistication of the software also demands the same from its hardware. Powerful AI systems typically are run through hardware like a GPU (graphics processing unit) which facilitates the computation needed to run complex numerical tasks. Competition has accelerated the development of these hardware technologies leading to exponential growth in their processing power and complexity. Hardware like the ‘AI accelerator’ develops in response to the increasing demands of digitization and AI processing.[24] GPUs and AI accelerators require a kaleidoscope of different materials to be built, including Cobalt and Tantalum.[25]

This suggests that the demand for these raw materials will only continue to grow. While concerns have been expressed over sourcing materials by the EU and independent organisations like the Global Battery Alliance, not much effort has been put into relieving the socioeconomic difficulties posed on countries like the DRC. As we were told by Pacifique, “the country, the population, the people, the lower classes should also benefit from this digitalization, from the exploitation of raw materials within the country. There should at least be a social responsibility to ensure that the population sees the point of exploitation”. It does not suffice to simply draft ethical guidelines for the exploitation of raw materials. Rather, concrete action needs to be taken directly on the ground where the socioeconomic struggles and existential threats are present and to ensure that the wealth and safety of the Congolese people are prioritised.

What does this mean for our perspective on the EU ‘twin transition’ and more broadly for political actors in the Global North?

The Kivu in Eastern DRC is one of the many sacrificed zones in the global capitalist economy. Its people and environment bear the cost of the green and digital transition, as the increased demand for raw minerals fuels armed conflict, exploitation of its rural population and extractivism in its soil. The economic interests at stake override the political will to build sustainable peace in the region, and the global capitalist system prevents Congolese people from building local and community wealth. The Pan-Africanist perspective, as defended by the Comité Ujamaa, highlights the need for African solidarity and unity to resolve the armed conflict and plunder in the Kivu. For the transitions to renewables and digital technologies to be truly just, the countries with critical minerals in their soils need to build the political, economic and legal power to engage in international trade on their own terms.

Congolese activists protest in South Africa, Image by Mzi Velapi[26]

For political actors in the Global North, we need to take responsibility for the communities that bear the costs of the economy we are building. We need to campaign against abusive trade agreements and against the financing of military operations that further destabilise the Kivu. We need to advocate for reparations for the regions that have historically suffered from our economic development. And we need to strive for a post-growth economy; as building more sufficient economies in Europe reduces the pressure that our unbridled consumption and production puts on resources and labour in the Global South. The EU twin transition – digital and energy – must go beyond growth, or it will perpetuate human suffering and environmental destruction inside and especially outside of its borders.

At Commons Network, we are trying to disseminate this vision for global justice: degrowth and democratic economies in the Global North—and delinking and economic sovereignty in the Global South. We believe that one cannot happen without the other, and that climate justice certainly cannot happen without either. Through our work with the Post-growth Pan-European network, we discuss political strategy and policy tools with elected representatives to build a post-growth European economy, and ultimately to halt European exploitation and extractivism, on its land and elsewhere. And through our Digital Commons project, we are exploring alternative avenues to big tech monopoly.

-

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/21/a-guide-to-the-decades-long-conflict-in-dr-congo#:~:text=Approximately%20six%20million%20people%20have,internally%20displaced%20in%20eastern%20DRC. ↑

-

Coltan is the raw ore harvested and later refined to Tantalum. ↑

-

“As much as 70 percent of the world’s cobalt supply comes from the DRC. Coltan, used in gadgets like PlayStations and phones, is also plentiful in eastern DRC.” https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/21/a-guide-to-the-decades-long-conflict-in-dr-congo#:~:text=Approximately%20six%20million%20people%20have,internally%20displaced%20in%20eastern%20DRC. ↑

-

https://www.brusselstimes.com/956676/eu-condemns-rwandas-support-to-rebel-group-in-drc-signs-agreement-on-raw-materials ↑

-

Global Witness, (2004). Same old story – Natural Resources in the Democratic Republic of Congo. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/same-old-story-background-study-natural-resources-dr-congo ↑

-

United Nations, (2010). DRC: Mapping Humans Rights violations 1993-2003. Report of the OHCHR https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/CD/DRC_MAPPING_REPORT_FINAL_EN.pdf ↑

-

United Nations, (2010). DRC: Mapping Humans Rights violations 1993-2003. Report of the OHCHR. (pp. 17) https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/CD/DRC_MAPPING_REPORT_FINAL_EN.pdf ↑

-

Human Rights Watch, (2023). DR Congo: Killings, Rapes by Rwandan-Backed M23 Rebels. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/06/13/dr-congo-killings-rapes-rwanda-backed-m23-rebels ↑

-

https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2022/11/4/dr-congos-faltering-fight-against-illegal-cobalt-mines ↑

-

https://cega.berkeley.edu/assets/cega_research_projects/179/CEGA_Report_v2.pdf ↑

-

https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2022-05-03-research-paper-29-rev.pdf ↑

-

https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2022-05-03-research-paper-29-rev.pdf ↑

-

https://www.globalbattery.org/media/publications/WEF_A_Vision_for_a_Sustainable_Battery_Value_Chain_in_2030_Report.pdf ↑

-

https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary ↑

-

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/eb052a18-c1f3-11eb-a925-01aa75ed71a1 ↑

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214629618312246 ↑

-

M%20Act)%20will%20ensure%20EU,2030%20climate%20and%20digital%20objectives. ↑

-

https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/trade-raw-materials_en ↑

-

https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/europes-digital-decade-digital-targets-2030_en ↑

-

https://www.euromines.org/files/key_value_chain_electronics_euromines_final.pdf ↑

-

https://elitshanews.org.za/2024/03/19/congolese-in-sa-protest-drc-plunder-and-genocide/ ↑

☰

☰