Last month, our new colleague Winne van Woerden joined our team as a junior researcher. Winne will use the next half year to graduate from university and help us out at the same time. We are very excited to welcome her at Commons Network HQ. In this blog post, she introduces herself and her research topic.

Dear reader,

Before I share with you a problem that has been keeping me busy for quite some time now, I should first introduce myself to you. I’m Winne, 23-and-a-bit years old, and deeply enjoying life so far. The upcoming months I will be collaborating with Commons Network to graduate from university. I’m doing a masters in Global Health, an interdisciplinary programme combining international development with health sciences. I would highly recommend it to anyone interested in, well, basically the world and her overwhelming challenges that are all somehow connected to human health and well-being.

Trying to explain what Global Health is really about often leads to an unsatisfying discussion, so I was delighted when Editor-in-Chief of the Lancet and passionate Global Health advocate Richard Horton provided me a perfect one-liner to sum it all up, as he stated how:

“Global Health is an attitude – it is about the universal nature of our human predicament. It is a way of looking at the world, and a statement about our commitment to health as a fundamental quality of liberty and equity.”

This being said, here comes my problem.

While I consider myself a ‘true Global Health advocate’ with a strong sense of social justice, a dedication to health for all and an eagerness to talk about (or march for) the environment, the journey of my life took (takes?) place in one of the most affluent countries in the world: The Netherlands. This means that my believes, imaginations and culture have been shaped by the one main goal that dominates the majority of the Western world: the goal of unlimited growth.

Under predominant Western culture, growth in itself has now come to be an unquestioned imperative and a naturalized need for so many people, specifically for those belonging to my generation. Starting at the moment most of us in The Netherlands begin to grow up, we learn that constant expansion is good and logical and something to aspire. The logic of growth not only validates our sense of self-worth, it justifies our idea of nature as subject to humans. What’s more, we have been socialized to believe in the sacredness of technology and innovation, in the unlimited potential of human ingenuity and intelligence.

The results of such a growth-oriented vision on economic development and human progress have been tremendous – as has its impact on human health. At first glance, and according to many conventional development metrics, it seems that humanity is doing better than in any other point in history. Huge advances in public health worldwide have created a surge in global life expectancy, more people have access to life-saving medical products, fewer young children are dying. It is not hard to paint a bright and prosperous picture of the world these days. Without talking down these tremendous improvements, I have come to the realization that all of us who have become addicted to growth are facing an enormous challenge looming in front of us.

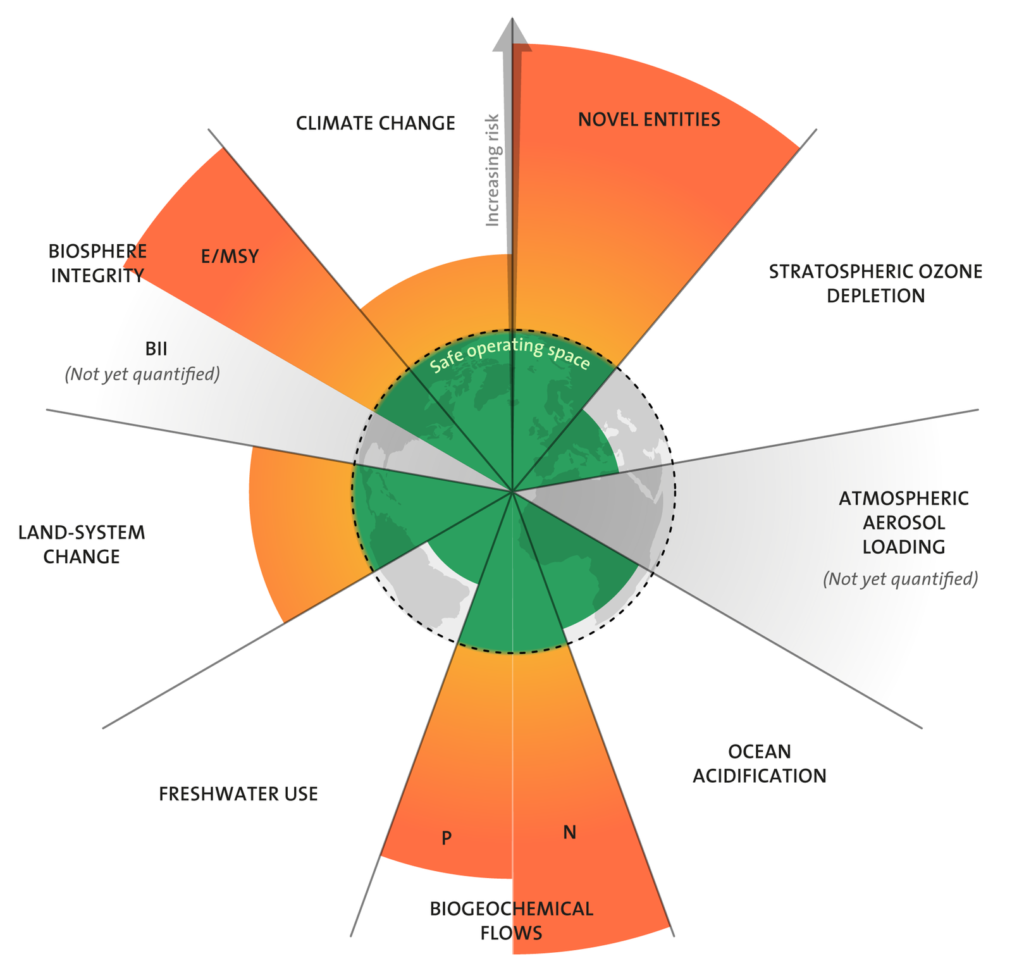

Humanity’s progress has come at an enormous cost for the planet. Warnings about ecological breakdown have become ubiquitous. In order to ‘develop’ ourselves as a species, we have been pushing the natural systems of Earth into a state of distorted unbalance. Four out of nine so-called ‘planetary boundaries’ (which the scientists introducing the concept defined as ‘the ceilings of a world considered to be safe for continued social and biological well-being for humans’) have been crossed now. In a single life time, humanity has become a ‘planetary-scale geological force’. Many scholars all across the academic spectrum are labelling the current geological epoch as ‘the Anthropocene’ (as opposed to the Holocene), acknowledging the role human activity is playing in the current state of the Earth.

Meanwhile, with the expansion of global wealth and the proliferation of growth-oriented capitalist economics, wealth concentration and global inequality has increased considerably. In short, it seems to me that it’s high time to make growth unlogic.

But how?

Much time by so many has been spent already on the pursuit to answer this question. Yet, the range of proposals and ideas varies greatly, and there are still some major gaps in knowledge waiting to be filled by eager thesis-writers like – yup – myself.

So when I was about to write my masterthesis for Global Health, eager to contribute something to the academic explorations of viable pathways that may help steer humanity into the direction of an ecological sustainable and socially desirable future, I knew I wanted to focus on alternative narratives that move beyond growth.

And that’s how I arrived here, at Commons Network. To learn if and how, within a growth-addicted society like we have in Europe, we (including myself) can disregard the quest for growth without compromising on health equity. I will (since theories are sacred in thesis-land) dive into the core theory behind the argument to do so, ‘Degrowth’, which may be defined as

‘the purposeful downscaling of production and consumption patterns which would enhance ecological conditions while increasing human well-being and social justice on the planet’

My main focus will be on the relationship between degrowth and human health and well-being. If we are to accept degrowth as an enlightened response in the West to the reality of ecological overshoot and the global deterioration of the planetary biosphere, how would this manifest itself into the field of global health? Put differently, are we still able to secure human health and well-being in an equitable way when respecting the fact that we live on a finite planet? And how?

If our current frames about human health and well-being, based on the growth-ideology, are only steering us into a trajectory geared towards collapse, how then to (re)define health, illness and caring along the lines of degrowth thinking? Finally, it becomes clear how, in a degrowth society, huge institutional changes would be needed to promote and protect human health equitably. What might our health system look like and what new roles for the state, the market and the commons would emerge out of degrowth thinking?

With these questions in mind (and more), I will try to find those people who are putting the alternative and often regarded as ‘utopian’ theory behind degrowth thinking into practice: commoners. The upcoming months I will explore if and how the values and ideas behind the practice of ‘commoning’ can help in formulating answers to these questions.

It is clear that a socio-ecological transformation as proposed by Degrowth advocates is very challenging. The French Degrowth champion Serge Latouche has put it quite accurately:

“The tyranny of growth-focused economic and societal thought has made imaginative thinking outside the box impossible”

With regards to making this transformation in the field of Global Health, the vision on human health and well-being behind ‘commoning’ and the caring practices it is linked to may very well open up the space for such urgently needed imaginative thinking in our ‘advanced’ Western world, so that we can make growth unlogic in a fair and just way and reposition human flourishing within that of the planet as a whole.

☰

☰